Language keepers of Turtle Island

|

Introduction

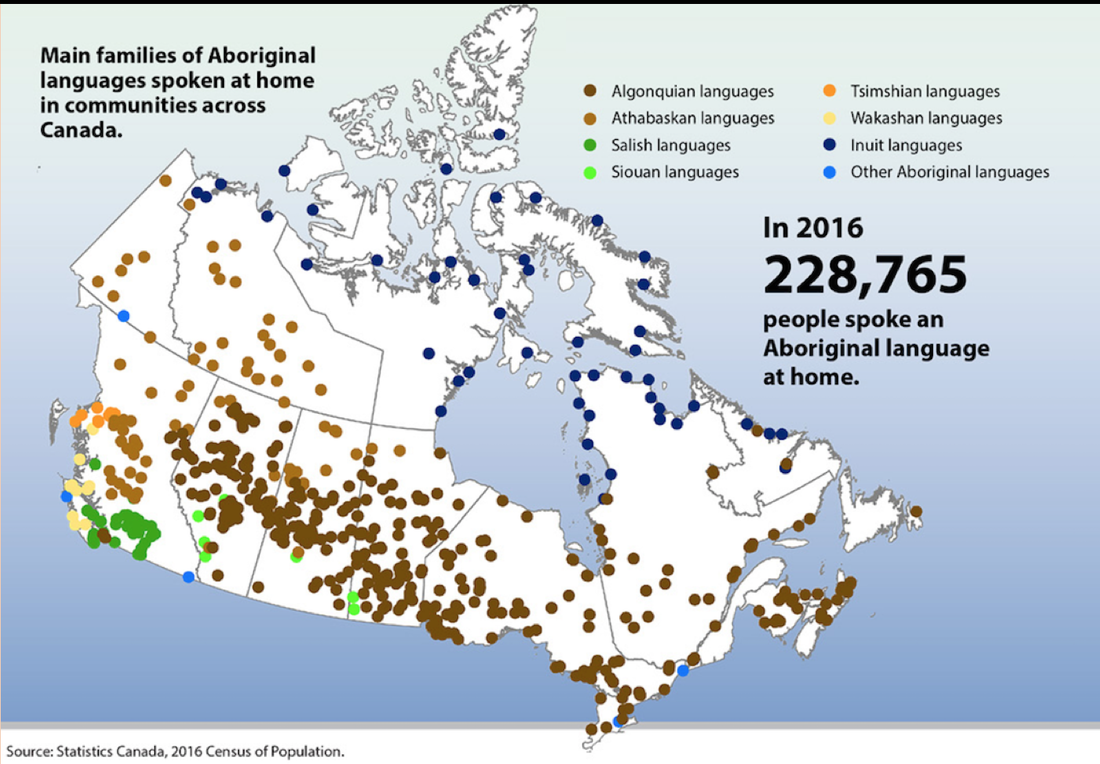

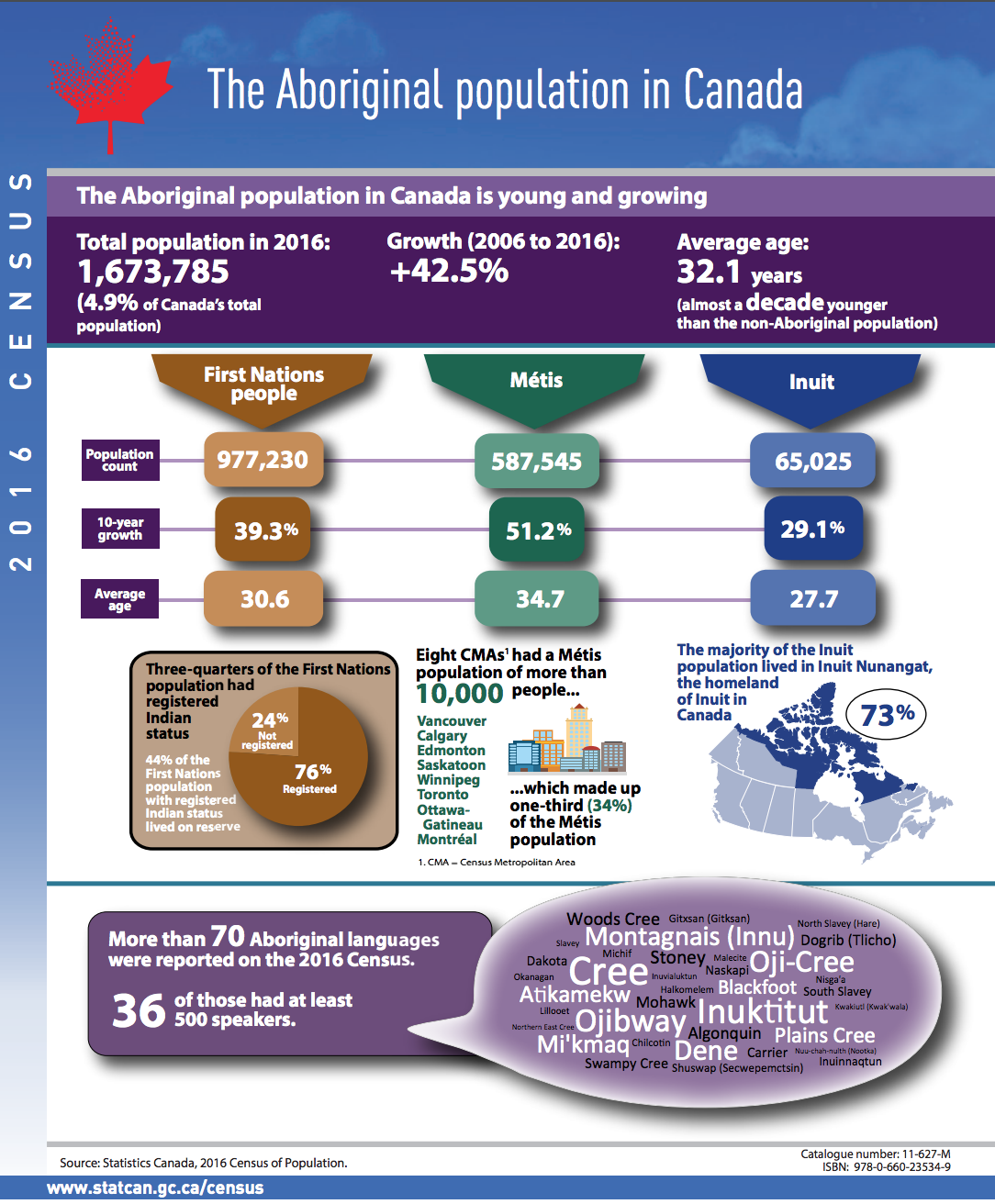

The map on this page shows the expansive distribution of Indigenous languages across this country. More than 70 languages, grouped in a dozen language families, are still alive despite repressive government policies in the past 150 years that put them at grave risk. That so many languages have survived across the land now called Canada is a testament to the strength and resilience of Indigenous communities. It speaks to the resolve and perseverance of language keepers who safeguarded their besieged languages, against the odds. The run-up to the promised Indigenous Languages Act of 2018 seems a good moment for all Canadians to become much more familiar with this country's first languages and their protectors. This blog showcases the work of unsung language heroes whose contributions are not widely known. Indigenous Elders and scholars doing invaluable work far from the limelight have helped inspire a growing number of young people to learn the languages of their communities. Technology can support language revitalization in important ways, but ultimately it is people who save languages. Photo credit: Banner image of Thirteen Moons, by Dene and Anishnaabe artist Alex Janvier, photographed by Akaash Maharaj

|

Blog post #1: Onowa McIvor

|

Onowa McIvor is director of Indigenous Education at the University of Victoria and president of the Foundation for Endangered Languages Canada. Her research focuses on adult Indigenous language learners, and particularly the mentor-apprentice method that pairs a learner with a fluent speaker. Her 2012 PhD dissertation, îkakwiy nihiyawiyân: I am learning [to be] Cree, included an autoethnographic account of her own 12-year language journey, which she documented through journal writing.

She is now leading a major project called NEȾOLṈEW̱ (meaning "one mind, one people" in SENĆOŦEN, one of the dialects spoken by the WSÁNEĆ (Saanich) Nations of southern Vancouver Island). This six-year collaboration brings together nine Indigenous groups across the country to build a language revitalization network focused on adult learners. Learn more about the SSHRC-funded NEȾOLṈEW̱ project (and an earlier phase in British Columbia): |

All Canadians need to learn about the land beneath their feet, learn about the First Peoples whose land they live on. |

Blog post #2: Patricia Ningewance Nadeau and Jerry Sawanas

|

Patricia Ningewance Nadeau teaches at Algoma University in Sault Ste Marie, Ontario. She is a residential school survivor from Lac Seul First Nation who has worked to preserve Ojibwe for more than 35 years. She is also an artist and founded a company to publish and market her books, CDs and cards, as well as those by other Indigenous language speakers. (See her Mazinaate website and brochure.)

Her Pocket Ojibwe, A phrasebook for nearly all occasions, has been translated into other Indigenous languages and her Ojibwe primer, Talking Gookom's Language, aims to help young people communicate with their grandparents. She told CBC Radio's Unreserved that to learn the language of their community, Indigenous youth should keep it fun, learn from Elders and other proficient speakers, and feel confident that they can do it. |

|

|

Jerry Sawanas, from Sandy Lake First Nation, is a senior broadcaster with the Wawatay Radio Network in Sioux Lookout, Ontario. An Oji-Cree language expert, he translated Pocket Oji-Cree, the fourth language version of Patricia Nadeau's Ojibwe phrasebook.

For us, where we learn best is on the land. The land teaches you everything. It teaches you how to survive. It teaches you how to take of yourself out there. ... Your education, that's where you get it from. |

|